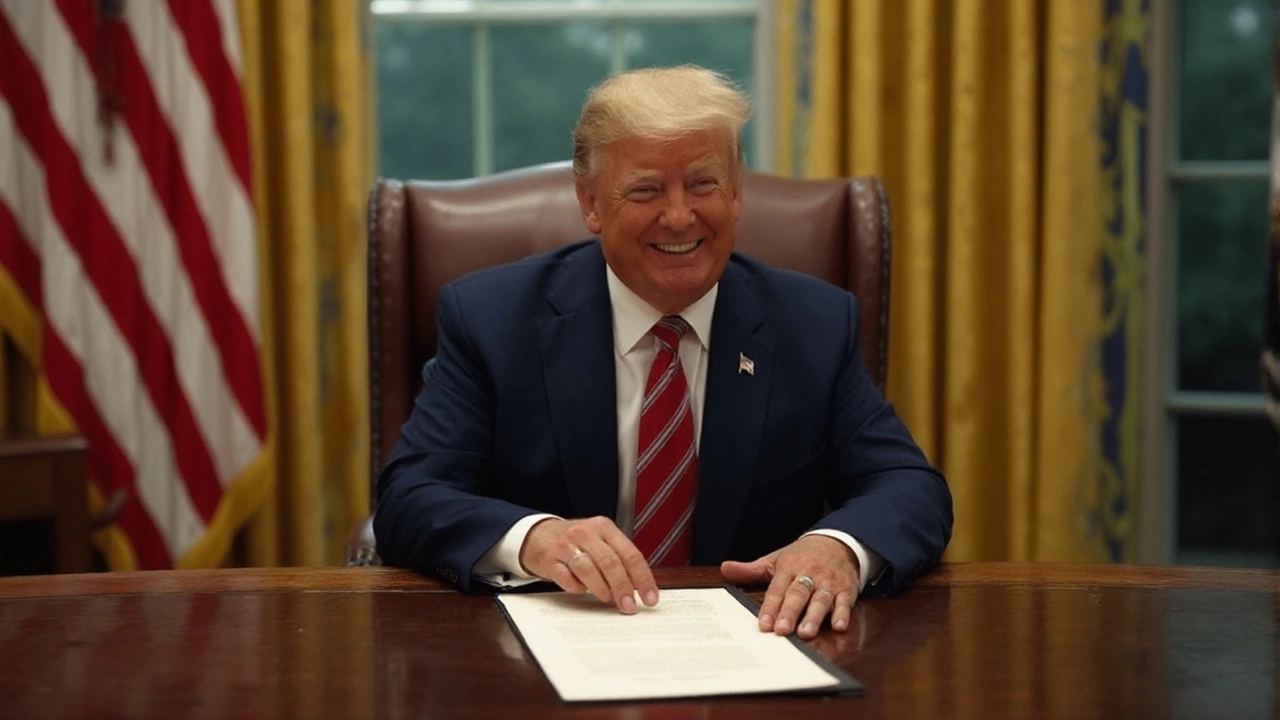

One day into his second term, Donald Trump did something no modern president has attempted: he used the pardon power to wipe away or reduce penalties for almost an entire class of federal defendants. The January 6 pardons and commutations—nearly 1,600 in total—instantly reshaped the legal and political landscape around the Capitol attack. Trump signed the orders on January 20, 2025, held up the black folder for cameras, and called the defendants “hostages.” A years-long criminal effort by the federal government ended in minutes.

The numbers capture the scale. Most of those charged in the Capitol riot received full pardons. Fourteen people convicted of seditious conspiracy—among the toughest charges brought—had their sentences cut. That group included leaders of the Proud Boys and Oath Keepers, organizations prosecutors said played central roles in coordinating the breach. One of them, former Proud Boys chairman Enrique Tarrio, who’d been serving a 22-year sentence, was moved for release, according to his attorney.

The Justice Department, signaling a wide interpretation of the orders, told courts and defense lawyers that coverage reaches beyond the immediate melee. In at least one case, it said the clemency extends to Jeremy Brown, a retired Green Beret serving time not only on January 6-related counts but also for possessing illegal weapons and retaining classified military documents. The message was clear: the administration wanted a clean slate for the federal January 6 docket.

This wasn’t a surprise. Trump telegraphed the move for months, promising mass pardons on “day one” except for those he called “radical” or “crazy.” Vice President JD Vance had earlier pushed for selective clemency for “peaceful” protesters. Once in office, he backed the broader sweep.

What exactly did the clemency do?

Let’s separate the legal mechanics from the politics. The Constitution gives a president broad power to grant reprieves and pardons for federal offenses, except in cases of impeachment. That authority is nearly absolute. Courts rarely step in.

Two tools were used here: pardons and commutations.

- Full pardon: Forgives the federal crime and clears remaining punishment. It doesn’t erase the fact of conviction from history or news archives, and it doesn’t automatically restore all civil rights, but it ends the criminal consequences at the federal level.

- Commutation: Reduces the punishment—usually the prison term—without vacating the conviction. Fines and restitution can also be remitted if specified.

Trump’s orders did both. The vast majority of defendants—people convicted or still awaiting trial for offenses tied to the Capitol breach—received pardons. Fourteen people convicted of seditious conspiracy saw their sentences cut. Those are the defendants prosecutors said helped plan or lead the effort to stop Congress from certifying the election results.

By the time these orders hit, the federal January 6 caseload had become one of the largest in U.S. history. Nearly 1,600 people had been charged in all. According to case tallies cited by federal officials, more than 600 had convictions for assault or obstruction of officers, and about 170 were convicted of using deadly or dangerous weapons. The median prison sentence was 240 days. The attack left roughly 140 officers injured and caused at least $2.9 million in damage to the Capitol complex.

The orders did not touch state prosecutions or civil lawsuits. If a defendant faced state charges—for example, trespassing, assault, or weapons violations under state law—those cases remain a state call. Nor do pardons block civil claims. Estates of officers, members of Congress, staffers, and journalists who were harmed can still sue. On the federal side, the Bureau of Prisons and U.S. Probation moved quickly: releases, supervised release terminations, and case closures began within hours.

A few more practical points matter:

- Pending cases: Prosecutors asked judges to dismiss federal charges covered by the orders. Defendants awaiting trial were released from pretrial detention unless they were held on unrelated matters.

- Appeals and post-conviction motions: Those ended for pardoned offenses. Courts generally mark them moot.

- Restitution and fines: If the order covers them, agencies stop collection and refunds are possible. If not, victims can still press for payment in civil court.

- Firearms rights: A pardon can remove federal disabilities tied to a conviction, but practical restoration is complicated and may still trigger other state or federal restrictions.

- Admission of guilt: In U.S. law, accepting a pardon is traditionally treated as an admission of guilt. That’s not just trivia; it can matter in civil suits.

Some of the most contentious recipients were members of groups with track records of political violence. Monitoring by GLAAD documented nearly 70 anti-LGBTQ incidents tied to the Proud Boys since mid-2022, including more than 50 protests targeting drag shows and school boards, and at least four incidents that turned violent. Critics said handing out clemency to leaders with those histories crosses a line: it normalizes intimidation as political expression.

Public reaction was swift. An AP survey found only 2 in 10 adults supported the pardons. More than half opposed them. Civil rights groups called it an abuse of power. Maya Wiley, who leads The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, accused the administration of “giving permission to vigilantes” and “sowing fear.” She pointed to Trump’s own words on January 7, 2021—“if you broke the law, you will pay”—as a contradiction.

Trump’s allies celebrated the move as overdue justice. In their telling, the justice system came down harder on January 6 defendants than on other political unrest cases, and the president corrected that imbalance. That argument is now central to the narrative the White House is building around the pardons.

To understand the scale, it helps to look back. Presidents have issued controversial mass clemencies before: Gerald Ford’s pardon of Richard Nixon in 1974; Jimmy Carter’s 1977 amnesty for Vietnam draft evaders; periodic drug-sentencing commutations under both parties. But those were narrower in scope or targeted different kinds of cases. Using clemency to end an active, sprawling criminal investigation into an attack on Congress is something new.

Legally, the power is wide. Politically, it carries a bill. The Justice Department must now unwind hundreds of prosecutions. U.S. attorneys will file dismissal notices. Probation officers will close files. The FBI, which spent years combing through social media, phone records, and travel data, will stand down on hundreds of open leads. A law-enforcement effort that spanned every state and involved thousands of agents, analysts, and prosecutors is, functionally, over.

Inside DOJ, the shake-up went beyond the pardons. The administration removed officials who worked on criminal cases against Trump and announced new probes of “political opponents” under an executive order titled “Ending the Weaponization of the Federal Government.” Career civil servants have legal protections from political retaliation, so expect clashes with inspectors general, the Office of Special Counsel, and the Merit Systems Protection Board over how far the White House can push. Those fights won’t be settled in a press release; they’ll move through internal processes and, likely, federal court.

For people on the ground—defendants and families—the change is immediate. Inmates call home. Half-finished plea talks stop mid-sentence. Defense lawyers file boilerplate motions to dismiss. Some clients who spent months in jail now walk free. Others, who had already completed sentences, will ask courts and agencies to lift the lingering burdens of a federal conviction: travel blocks, housing problems, job barriers.

The ripple effects also hit victims and witnesses. Officers who took beatings inside the tunnel on the west side of the Capitol and along the east steps now watch the cases they followed end on a stroke of a pen. The same is true for staffers evacuated that day and journalists assaulted as they tried to work. Restitution orders may be lifted if covered. Civil cases may take on new urgency—because the criminal track is closed.

There’s also the question of deterrence. Prosecutors often talk about “specific deterrence” (stopping the person who was punished from reoffending) and “general deterrence” (sending a message to everyone else). Pardons undercut both. Opponents say the message now is that political violence carries little risk if your side wins. Supporters argue the message is different: that protest, even when it spills into crime, shouldn’t be punished with what they view as selective zeal. These are not academic debates; they shape what people believe is possible in the next big street confrontation.

One more thing: federal clemency doesn’t rewrite history. It ends punishment. It doesn’t erase video evidence, sworn testimony, or certified judgments. It doesn’t block committees of Congress—or future ones—from investigating. And it doesn’t stop states from bringing their own cases, which rely on separate laws and prosecutors.

What happens next?

Short term, this becomes a logistics story. The Bureau of Prisons releases people. Marshals undo detainers. Probation offices close files. Prosecutors and judges clean up dockets. The Clerk’s Office in D.C. federal court will process a wave of orders all at once. Expect administrative bottlenecks, especially on Fridays and holidays when releases stack up.

Medium term, it’s a legal story. Even though the pardon power is broad, there will be challenges around the edges. Defense lawyers will test whether the text covers every relevant charge in each case. Prosecutors will push back where language is ambiguous. Courts will sort it out. There may also be fights over people with mixed case histories—some counts covered by clemency, some not. Judges don’t love messes like this, but they’ll resolve them one by one.

There will also be fights over government jobs. Removing career officials who handled cases involving Trump raises civil-service issues. Those aren’t quick. The Merit Systems Protection Board and Office of Special Counsel exist for moments like this. Their rulings can lead to reversals, reinstatements, or settlements—and more headlines.

Politically, Congress will move. Members will demand records: drafts of the clemency orders, emails, and the internal DOJ guidance that told prosecutors how to apply them. Expect subpoenas and standoffs. The White House will claim executive privilege. Committees will threaten contempt. That script is familiar, and it ends in court more often than not.

Lawmakers will also look for legislative responses, even if they’re symbolic. Some will propose limits on the pardon power in cases tied to insurrection. Those bills face long odds; changing the pardon power would likely require a constitutional amendment. Others will push for new federal crimes or sentencing rules that apply when violence targets democratic processes. Whether any of that becomes law is a separate question.

The public dimension matters too. An AP poll showing only 20% support gives Democrats and some Republicans a data point to organize around. Expect campaign ads that feature body-cam footage, court transcripts, and statements from injured officers. On the other side, expect testimonials from defendants who say they were overcharged, received harsh sentences, or were kept in punishing conditions before trial. Both narratives were already live before the orders. The pardons crank up the volume.

Victims’ lawyers will adjust. If criminal restitution goes away, they’ll rely more on civil claims for damages. They’ll cite evidence from the criminal cases—photos, texts, and expert reports—and argue that the standard in civil court (preponderance of the evidence) is lower than in criminal court (beyond a reasonable doubt). Defendants who accepted pardons may face tough questions in depositions because of the “admission of guilt” doctrine tied to clemency.

Internationally, foreign governments are watching the domestic reaction more than the legal fine print. Allies that rely on the U.S. model of peaceful transfers of power will study this for lessons. Authoritarian rivals will use it in propaganda. That cycle is predictable, but it still affects how America is seen abroad.

Inside the building at First and C Streets, where D.C.’s federal court sits, the mood is different: relief, frustration, and routine all at once. Some prosecutors spent years on these cases. They’ll box up files and move to new assignments. Judges will close dozens of cases in quick bursts. Defense lawyers will spend the week explaining to clients what a pardon changes and what it doesn’t. The system moves on, because it always does.

There’s a larger memory fight brewing. How January 6 is remembered now pulls even harder in two directions. One side will point to clemency as proof that the system plays favorites. The other will argue the system had gone too far and that a course correction was necessary. Museums, textbooks, documentaries, and political rallies will all tug on the same rope. The law can settle cases. It can’t settle memory.

For now, the headline is simple: on day one, Trump used the most powerful pen a president has to upend one of the biggest criminal dragnets in U.S. history. The legal clean-up is underway. The political and cultural fights are just getting started.